The Realism of (Science) Fiction

Science fiction in general and Star Trek in particular is frequently the target of reproaches of not being serious or not being realistic. Criticism even comes from highest places. Rick Berman, then Star Trek Executive Producer, stated in an interview with Star Trek Monthly: "I have been opposed to gag reels simply because Star Trek is something that always borders on the silly... You've got people flying at impossible speeds and spaceships defying gravity. You've got a lot of things that are accepted, but that are almost scientifically ridiculous. It's so easy to turn it into a parody."

With Star Trek "bordering on the silly" anyway, are we expected to consume it only as mindless entertainment? I wholeheartedly reject such a stance. Although I agree that entertainment is still its primary goal, I see science fiction on par or even as more intellectual than most fiction set in our "real" world. Actually, I suspect that many of the critics and even Rick Berman himself may have a problem with understanding the genre.

In my view it is vital to reconsider and refine common ideas of "realism" when viewing or reading fiction of any genre. Here and elsewhere on my website it is not my principal intention to disprove the detractors of Star Trek. It does not bother me too much, and I have created the site least of all for them. My line of reasoning is that between the two extreme positions taken by critics (the mere ignorance on one hand and the "scientific" over-analysis as the other extreme) there is a "level of consistency" where Star Trek is both entertaining and educational - and a subject worth being scrutinized. This is exactly the level I strive to reach and maintain at EAS.

Many of the following considerations may apply to TV shows, movies and literature alike. But with the case of Star Trek in mind, I will focus on the fiction on the small and the big screen.

Fiction and Science Fiction

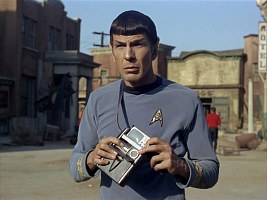

It is a trivial prerequisite to recall that almost nothing shown in a movie or a TV drama is authentic. The characters were conceived by writers. They don't exist in reality. They are played by actors who, in their real lives, may be individuals contrary to their roles. They run around in sets that only look authentically solid, but are made of plywood and cardboard instead of stone or steel. Even expensive movie productions are customarily not filmed on location, unless the intended place happens to be near Hollywood or wherever the studio is located. Very often when a piece of technology is involved, it is only a prop without a function. Hardly anything on screen, regardless of where and when the series or movie is set, is meant to be watched with all this knowledge in mind, because it may spoil the fun. The viewer is tacitly requested to suspend disbelief to a certain degree.

Still, it is necessary to plan the production of a TV series or movie in a way that it does not show anything that could appear implausible, improbable or even impossible. No fiction can be perfect in this regard. Fiction, irrespective of its genre or artistic quality (and TV shows just like literature), is always something devised to catch our interest, to show something that is unusual and that would not occur to us in every-day life. Even and especially the so-called "reality TV" frequently creates contrived situations that don't comply with real experiences.

The subject in the following is how we may identify and how we should weigh the criteria for what is implausible, improbable or impossible enough to impair our suspension of disbelief. As already mentioned, almost every fiction customarily strives to overstate and to put emphasis on the extraordinary. There are also TV series of all genres, not only comedy, that are deliberately made without continuity and hence in a way not to be taken seriously. An extreme example is "South Park" where Kenny, with exceptions in more recent episodes, is killed every time.

But what are the qualities a TV drama or a movie must have in order to appear realistic? It seems that a drama set in our present world and time has the advantage that it apparently shows people, places, objects and situations that we are familiar with from our every-day life, that appear realistic just because we think we known them. In this sense some critics go as far as rejecting any kind of science fiction because, in their opinion, it shows an utopian world and, in particular, science and technology that deviates from what they think is correct. Therefore, already the basic setting of science fiction as something that does not exist in our world or time should fall under the category "impossible" in their view. They don't manage to suspend disbelief. But I think many of them don't really attempt to. Moreover, I am surprised that so many laymen out there seem to have the knowledge in physics and engineering that would allow them to recognize fictional technology as unattainable along the lines of "impossible speeds and starships defying gravity". Ironically, the share of science fiction fans among real-world scientists and engineers seems to be much higher than among the "ordinary" population.

Defending science fiction as something to be taken at least as seriously as other fiction, I may throw in countless examples where other genres become unlikely or just silly, beyond the perhaps necessary exaggeration of normal life. It is just not plausible that every few weeks in a soap opera someone has a car accident, is arrested or turns out to be related or not to be related to someone else. Not only the storylines on the whole, but also details are often anything but realistic. No human being could take so many beatings as action heroes usually do without being knocked unconscious. Unlike it would be in reality, movie cars never get stuck when they crash into other cars but they jump over them, and we can take for granted that they go up in flames. Computers on TV never have Windows installed but usually a strange hybrid of MacOS and MS-DOS with huge pixelated fonts. As soon as a 3.5 inch floppy disk has been inserted into a movie computer, a program launches automatically and displays well-formatted data without requiring any input. Finally, movie modems from the 1990s never allow more than one character per second if the transmission is plain text, but recordings of observation cameras can be downloaded in two seconds, with ultra-HD resolution that allows to zoom in 800% and still have a sharp picture.

The list of common clichés that defy reality could be continued indefinitely. No TV series or movie is completely free of them. There are many examples of "real-world" fiction that undoubtedly destroy their own credibility. Just like the infamous "Bobby Ewing in the shower" reset button. Or the most atrocious offense against the laws of physics and common sense in any major movie: the ludicrous action sequence in "Mission Impossible (1996)" with Tom Cruise on the roof of an oddly diesel-powered "TGV" high-speed train, which is pursued by a helicopter through the Channel Tunnel with two-way traffic. Hence the title of the movie, I suppose. The sequence was so incredibly daft, we bubbled over with laughter in the theater! These examples demonstrate that even an purportedly "realistic" drama set in our world and time doesn't actually show the real world and often doesn't even try to get the very basics right.

"This fairy-tale is nonsense because a fox can't speak. And Star Trek is all crap because its technology will never work." Such are commonly uttered preconceptions. But bearing in mind that every fiction intentionally or inadvertently deviates from our every-day experiences, the only difference is that science fiction, just like fantasy too, does this already in its general setting of place and time. Within the boundaries of such a setting, science fiction may be even more realistic than much of what has a present-day setting. Rather than the mere knowledge about what is right or wrong, enjoying it is a matter of personal perspective and preference. This may be actually the reason why so many scientists are fascinated by Star Trek, even though and just because they know that not everything can work the way it is shown. In brief, fiction does not have to be "realistic" in a narrow sense to make a point or to be inspiring or entertaining.

Criteria for the Assessment of Realism

There is certainly no clear line between "realistic" and "not realistic" in fiction, and often not even one between "correct" or "false". Whilst everything said or shown on screen is a priori canonical, it may be subject to interpretation what we are supposed, allowed or willing to see in it. In ascending order, the following criteria may contribute to our impression particularly of a science fiction show like Star Trek. But they should not be taken as a strict set of rules.

Trivial errors

It is admittedly a matter of interpretation what kind of goofs may be regarded as trivial enough not to impair our suspension of disbelief. But bloopers, as unintentional imperfections, should fall into this category. For example, props that magically vanish and reappear, mirror-inverted scenes or recognizable stunt doubles, all of which happened several times especially in TOS. Much of this may appear logically and physically impossible. It may serve as a measure for the quality of the production, as the so-called continuity errors are only a matter of craftsmanship and may be avoided with sufficient carefulness. On the other hand, bloopers have hardly any impact on the story's credibility, and they may occur in TV dramas and movies other than science fiction just as well (I am just thinking of the countless times the microphone was visible in "Pretty Woman"!). We need not and would not make up explanations or excuses but are satisfied with the real-world reason that it's only a show with all of its typical shortcomings. In other words, we tend to ignore them and replace them in mind with what we are supposed to see.

Note In moviemaking terminology, such small mistakes are referred to as "continuity errors" while here at EAS I usually speak of continuity as intra-episode, intra-series and inter-series continuity.

Visual and aural effects

Another group of problems consists of the shortcomings of visual and sound effects. Such "effects" in the broadest possible definition may include virtually every phenomenon perceptible on screen, be it deliberate or not. A camera, for instance, does not show the same as a human eye would see, and our own visual perception may deceive us as well. The probably best known example is that wagon wheels with spokes may look like they turn backward, depending on the frame rate of the movie relative to the number of revolutions of the wheel. Clearly this is an unwanted effect. We easily accept this small flaw of movie production. No one would go and claim that in the 19th century wagon wheels did actually spin in reverse direction and make up explanations for that. There are other examples that we see or hear something that is not supposed to be in the real scene. For instance, there is the deliberate use of slow motion or blurring in movies, lens flares or wide-angle lens effects that wouldn't allow a proper assessment of sizes and distances. Also, sound or voices carried over from one scene to the next or the omnipresent background score. We may ultimately even put the "sound in space" phenomenon into this category.

It is obvious that intentional visual effects in science fiction have to be created with the means of present-day technology and with a limited budget. For example, any weapon beams are not produced with "real" phasers, disruptors or lasers. The light effects are just inserted into a completed scene. Strictly speaking, we wouldn't even see lasers in space because it is devoid any medium that could disperse the light into the direction of the camera. But aside from that, the beams might at least be created in a fashion that we wouldn't be able to track how they travel towards their target. Artistic license or negligence, however, customarily lets the beam appear to be slower than light. Some fans go as far as analyzing scenes frame by frame to determine the apparent speed of such a phaser or laser beam. But are we supposed to watch movies or TV like that? Certainly not. In the best case, a motion picture or TV episode is produced to appear just plausible when viewed under "nominal conditions", i.e. with normal frame rate and without frequent rewinding. And most importantly, without paying more attention to tiny details than to the intended focus of interest. What matters is that a weapon is fired and that it has a certain effect or not. This needs to be shown in some fashion, otherwise the series could go without visual effects. Spotting not-so-perfect effects may be fun in a sense of nitpicking, but it is irrelevant in the assessment of the realism of the show. Much less could this serve as "evidence" for power or speed figures of the starships if they really existed. Effects are not sufficiently considered in the sense of a simulation of the real thing, and their quality depends on the equipment, budget, schedule, knowledge and experience of the visual effects staff. Effects are not made by scientists, are not strictly based on real science, and should not be mistaken as such.

Dialogue

Spoken dialogue is the most important part of any TV or movie script. Much more than any gestures or actions or the look of the sets it determines the course of the plot. But as much as essential as the writing is on the whole, as carefully should single statements be treated. Characters occasionally say something logically or physically implausible or otherwise unfitting. For example, engineers may use senseless units like "watts per hour", or mispronounce familiar technical terms. It is obvious that something like that shouldn't happen, but we should concede that the writers or the characters may have a bad day. Moreover, on many occasions, especially whenever dates or figures were involved, the characters may have overstated them or not correctly recalled them. They may be taken as rough estimates at most, unless the situation or the person who states them (like Spock or Data) lets us expect more precise figures.

Surely Geordi would never consciously say "exceeding Warp 10" (TNG: "Where No One Has Gone Before"), knowing that Warp 10 is the absolute upper limit. But we simply can't exclude such glitches or maybe overstatements when someone is excited. The case is a different one with the definite "faster-than-infinite-speed" statement in VOY: "Threshold" that can't be explained away as something misspoken. Summarizing, while dialogue is very fundamental and more definite evidence than the special effects, the impact of single lines on the realism of a show need not be very strong. For starters, we should accept any statement made on screen in compliance with the canon policy. Only where dialogue conflicts with harder visual evidence or where continuity is impaired, we may need to re-interpret it. Such as in the cases where a discovery (of an anomaly, lifeform or technology) is unwisely declared the very first of its kind in TOS or TNG, not anticipating that the latest series Star Trek Enterprise would predate all such "first times".

Look and feel

This category consists of set, prop and costume design and make-up techniques. Like the visual effects, unquestionably all of this has been tremendously improved in the decades since TOS, and it has always been subject to fashion trends of the real world. Just like the miniskirts in TOS. Speaking of TOS, its simplistic sets and props with their cheap look are frequently criticized as little realistic. But the original Enterprise sets were state-of-the-art in the 1960s, as were the Voyager sets in the 1990s. Bearing in mind that a TV series is always made with present-day techniques and for a present-day audience, this is anything but a flaw. On the contrary, it would be sad if there were no progress in TV production in the real world or if it were ignored by the makers of Star Trek. It is not far-fetched to predict that the most recently created Star Trek sets that we perceive as futuristic today will look outdated in 20 years.

Many of the sets and props of Star Trek Enterprise have an apparently more modern look than those of the four series set 100 years later (TOS) or even 200 years later (TNG, DS9, VOY). This is a matter of continuity. It is a sign that we should not ignore the appearance of a series as if it were something superficial. But we must distinguish the mere look and the supposed function of rooms, devices and user interfaces. For instance, more buttons on a tricorder is not equivalent to "more advanced". And the absence of a warp core set in TOS does not automatically imply that the ship didn't have a warp core. Likewise, it is not a valid argument that Star Trek is less realistic than other science fiction only because heavy machinery is hidden behind neat panels (inside the ship) or flush hull plates (on the outside). For one, this is over-interpretation since it comments on something that is (deliberately) not visible. It is also unfair because it compares the traditional look of Star Trek dictated by the budget limitations of TOS to the expensive high-tech design of modern sci-fi series and movies.

The Abrams movies and ultimately Star Trek Discovery are a whole new ballgame in this regard. Their set, prop and make-up design deviates so dramatically from what was firmly established in the old Star Trek that it can't be excused as a simple visual update. If we are fair and go by the same criteria for visual continuity that we apply to previous Star Trek series, the Abramsverse and Discovery can only be realistic if each of them takes place in its individual "reboot universe".

Hard visual and aural evidence

Hard evidence is everything that can be seen on screen (unless it is declared a dream or a parallel reality). Especially whenever it is shown how technology works, this may be of importance to the realism of the show. There are certainly scenes which -aside from continuity problems- show scientifically dubious or even unworkable technology. Rather than any superficial beam weapon effect, it is implausible how such devices as the transporter or the universal translator could possibly work, also bearing in mind that they show up frequently. It is close to impossible to re-interpret or ignore them, since we know for sure that the transporter dissolves a person and the universal translator enables nearly immediate communication with previously unknown species. It is a similar problem with "softer" evidence. We are aware that frequently bridge consoles explode during an attack, as if high-power plasma conduits were routed right through them. Whilst this is not physically impossible, it must be described as silly. Summarizing, observation of such evidence may well contribute to the impression of realism or lack thereof. But a fair analysis would include the realistic examples too - only that naturally many realistic aspects go unnoticed, whereas errors are gladly singled out especially by those whose goal it is to discredit science fiction.

Curiously, as much as the critics mock the technology that is hidden behind panels, they also complain if it is actually shown or mentioned how it works, thereby creating a no-win scenario. But with regard to the warp drive and the power systems with their various parts, as contradictory impressions as some episodes may create of it, Star Trek can be glad to have such a technology full of interesting facets. The alternative would be a machinery whose components are never shown or talked about and which is hidden deep inside the ship, only to avoid any mischievous comments that it would not possibly work the way it is meant to. Pretending that something is unrealistic because we have seen how it works (or, the other way round, that something else must be realistic because it is never shown), is not only a lackadaisical way, it fails to recognize the requirements of science fiction. Science fiction is supposed to show bold concepts and to work with these concepts. Science fiction needs imagination, and not a corset of rules of what is allowed to be shown and how.

Plot logic

Plot logic, in any kind of fiction, is created as soon as it is written and therefore mainly lies in the responsibility of the screenwriters and the producers. It is not a matter of "physical correctness" in the first place whether an episode is logically plausible. As an example for missing plot logic, we may look at VOY: "Demon", where the ship runs out of fuel in interstellar space. The search for deuterium begins as late as the warp drive has already gone offline! Whilst any "hard" evidence is missing (die-hard critics might even praise it as particularly realistic that for once the ship is without fuel!), it is absurd that the captain would not take care of the fuel shortage and not even take notice of it, and effectively condemn the ship and crew to die in open space. A similar problem occurs in ENT: "Shuttlepod One", where no one on Enterprise even attempts to contact Reed and Tucker on the shuttlepod after the ship has left to take the shipwrecked aliens home. These are clear signs how ill-considered writing can impair credibility much more than any single statements, props or effects.

Continuity

Continuity is related to plot logic. The difference to anything discussed so far is that continuity only refers to the fictional level and not to any outward reference (like even real-world physics). In the case of Star Trek, we have to deal with no less than three levels of continuity: intra-episode, intra-series and inter-series. Generally, intra-episode continuity would be rather easy to maintain as everything is handled by a single writer or a small team. Still, there are often enough conflicting statements or events even within the same episode. In this regard, TOS: "The Alternative Factor" is clearly the by far worst episode ever made, where almost nothing goes together. Intra-series continuity, as I have to concede, has reached a quite satisfying level in Star Trek Enterprise because previous occurrences and mentions are frequently and mostly consistently referred to. Inter-series continuity, finally, is the hardest part, as it spans over 50 years and 600 episodes in the case of Star Trek. It is obvious that there are sometimes huge logical gaps and fans feel like a reset button has been pushed, but it is often possible to fill them with explanations, thereby creating "retroactive continuity". This is what I try to accomplish in the Investigations section at EAS, without resorting to mere speculation.

Concepts

The concepts of a science fiction show are usually not taken into account by its detractors at all or are simply refused in their entirety. Whether the basic setting of the show, the characters and the stories appear realistic may be much a matter of personal preference. But it should be recognized even by critics how science fiction shows continue to create visions. The most important visions are not in the field of physics and technology, as science fiction is usually not meant to be "science in fiction", but "fiction of science". In the case of Star Trek, the idea of the United Federation of Planets and the goal "to boldly go where no one has gone before" clearly supersede the importance of all science and technology. Star Trek would not be possible without inventions like the warp drive, but it is devised to be an entertaining show and perhaps a moral play at times, and not a slide presentation of the technology.

Still, scientific concepts are frequently cited by both the fans and the critics. Fans tend to overstate the feasibility of the depicted concepts, whereas critics deny that they make sense in the first place. Just like the transporter or the warp drive in Star Trek, which are cherished by the first and condemned by the latter. These positions will always remain irreconcilable, and any attempt to approach them in a more scientific way will almost inevitably lead away from the very topic of science fiction. The best-known examples are the musings by Lawrence Krauss, who outlines the principles of the "warp drive" and the "transporter" in his book The Physics of Star Trek. Krauss likes Star Trek. Nowhere in the book does he decry its concepts. But he digresses, and the devices he describes have almost nothing in common with the canon concepts devised in Star Trek, except for their names. Krauss looks at "science in fiction" rather than at "fiction of science".

Speaking of visions, especially TOS and TNG are often regarded as the prototype of modern science fiction and, moreover, as visionary when it comes to anticipate real-world developments. Clearly Star Trek did not predict or even invent cell phones or tablets, but it is clear that these technologies appeared in Star Trek long before they were available in the real world. Moreover, on the original Enterprise a computer system that managed all ship functions and provided access to the library was commonplace, technological developments that would come to fruition in the real world almost 30 years later and are still ongoing. In this regard even TOS has never lost its sense of realism if we forgive the series its simplistic special effects and finish of sets and props. I doubt that we can say the same of many other TV series.

Conclusion

The first purpose of my above musings is to provide a viewpoint from which science fiction and in particular Star Trek is at least as realistic as any series set in our real world. It is a matter of media competence to recognize that the merit of fiction does not lie in the very appearance of characters and things or in the literal meaning of the words. For science fiction fans, it is a small leap of faith to accept that aliens exist (even if they look much like humans - if at least their look remains consistent) or that starships can move faster than light (even though the scientific explanation may be shaky).

The second reason for this page is to serve as an introduction and reference for the Investigations section at EAS. It explains why my focus is on certain fundamental problems (like inter-episode continuity), whereas I am not so much interested in mere nitpicking (although it can be fun too).

There is no generally accepted recipe how to assess the realism of a science fiction show, and it is not my intention to impose one on the visitors of this site. It may surprise, but I don't even think it's worth while analyzing Star Trek or any other science fiction as systematically as I have outlined above - at least I don't feel like doing that. Hence, this page only demonstrates what we would theoretically have to take into account.

Whilst an "analysis" of Star Trek alone is already debatable, it is much less desirable to compare different sci-fi franchises under these conditions. I find any kind of "Myfiction vs. Yourfiction" controversies immature and unbecoming of true fans. The so-called "scientific" evidence brought forward in the "vs." debates is amusing at best - if only the debaters wouldn't insist on their own observations or even their own rules of debates being the one and only truth. In strong contrast to that, I don't claim that my findings concerning the subject of realism are scientifically correct. They just reflect how I see the shows and how I understand "suspension of disbelief". Of course, this doesn't preclude that I apply scientific principles where they are applicable and that I comment on scientific errors where I notice them.

But for all those who seek arguments pro or contra Star Trek as a credible show, it is important to keep an open mind. A fair view of science fiction should take into account more diverse types of evidence than a narrow-minded "reality check" against the knowledge of the beginning 21st century. We may find examples where the laws of physics were carelessly or even deliberately broken, but only in few cases this has an impact on the story (the most notorious example being VOY: "Threshold"). Everything else may be still ignored or explained away. As I see it, continuity and the presentation of credible concepts (also on the visual side) clearly outweighs evidence from single events or the visual effects of the show.

The perhaps most important finding is almost trivial. Science fiction is not supposed to reflect our real life. It is not even meant to be particularly scientific. This should be taken into account in order to avoid the error of over-analysis of side aspects. We may either enjoy the show as it is visible on screen, or we may take nerdy pleasure in identifying scientific or logical mistakes. But we should not stir up these two levels of looking at science fiction, or allow the latter to ruin the former.

See Also

What is Canon? - definitions, reasons, interpretations and the EAS canon policy

Visual Bloopers - funny mishaps and editing mistakes

Credits

Some screen caps from TrekCore.

Reset button: Bobby in the shower in "Dallas"

Reset button: Bobby in the shower in "Dallas"